Fifteen years ago, Jan Michael, an alto in my chorus, approached me to share that s/he identified as transgender and was beginning his physical transition by taking testosterone. I was clueless about the process but suggested that we check in every few months for a range check. Within the next year, to my amazement, Jan’s voice moved seamlessly from alto through tenor and eventually settled at a solid bass 2. Aside from learning to read a new clef, he experienced relatively few vocal issues in the process.

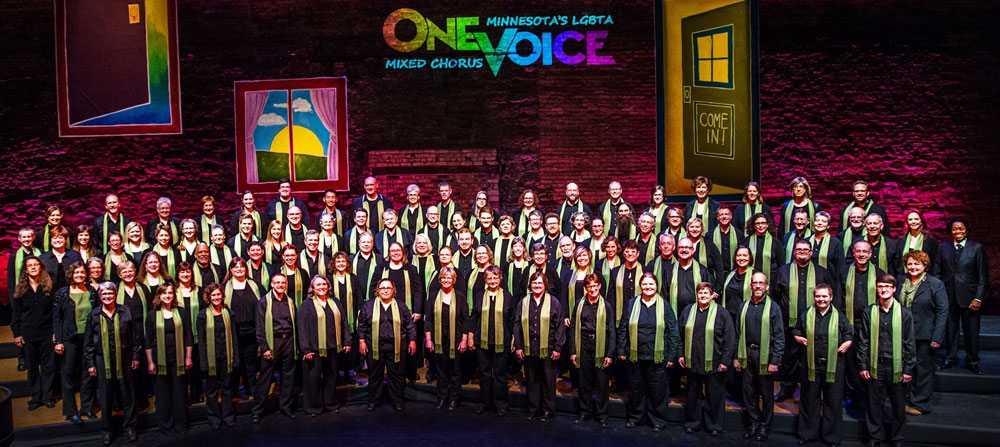

A year later, another singer in my chorus transitioned; this time, however, the process was much more complicated and included vocal fatigue, hoarseness, and serious difficulty singing. I was fascinated by the experiences of these two singers, and I felt helpless to address their vocal issues. I began reading and talking to vocal experts, and finally found one who had worked with transitioning singers. As a result of these conversations, my chorus, One Voice Mixed Chorus (Minnesota’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and allies chorus), hosted the world’s first Transgender Voices Festival held in St. Paul, Minnesota, in April 2004.

The day-long event included vocal workshops for transitioning voices, individual voice coaching, workshops exploring identity and voice, and training for voice teachers and conductors. A few trans* singers flew in from both the west and east coasts for our festival, and out of the event we birthed TransVoices, a new Twin Cities chorus for transgender singers.

Through these experiences, and through years of reading and conversations with trans* singers, I have come to understand that there are both similarities and differences between transitioning voices and the voices of cisgender boys in puberty.

But perhaps more importantly, I began to understand that voice is incredibly important to transgender people. The pitch of someone’s voice can determine whether or not they “pass” as their identified gender. Because transgender voices do not always “match” outward gender expression, trans* people may be silenced from speaking or singing out of fear or embarrassment. The situation is particularly sensitive for those transitioning from male to female (M2F). While synthetic estrogen creates some physical changes for a trans woman, it does not affect voice range. We may audition a singer who has wanted to live as a woman for perhaps her entire life, and has finally transitioned—but she may not be able to sing in a treble range. You can support her by listening to her voice and helping her to sing in a range that is healthy for her.

In One Voice Mixed Chorus today, around 10% of my singers identify as trans* or gender-queer. Our bass section leader is a trans woman with a rich low-bass range. I have several cisgender women who sing in the tenor section because that is their most comfortable range. I have a variety of genders in every voice part, so as a conductor I simply refer to my singers by voice (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) rather than by gender (men, woman, boys, girls, ladies, gentlemen). I also ask any guest conductor or clinician working with my chorus to also refer to voice parts rather than genders when working with our singers.

I asked several trans* singers to help me create a list of twelve tips for making a chorus more welcoming of trans* people. There are many ways that we as conductors can make simple changes to ensure that, as we create beautiful music, we are also creating choruses where people of all gender identities feel safe and welcome. ■

12 ways to make your choir more welcoming

- When posting for singer auditions, keep language about voice parts gender-neutral.

- In the audition setting, ask new singers their preferred pronouns, especially if a singer presents with an ambiguous gender.

- If a singer shares that they are transitioning via testosterone, ask when they started and how the transition has affected their vocal range, etc. It will typically take 8-12 months for an adult singer’s voice to settle to a consistent range and it can take up to two years for the voice to stabilize.

- Assign voice sections for each singer dependent on their voice range and color rather than gender. If a singer is transitioning, check their range every 3-4 months and assist them in moving to a new part as needed.

- You may encounter a trans* woman who wants to sing alto or soprano. However, unless she’s lucky enough to be a countertenor or has the finances to undergo vocal adjustment surgery, singing in a treble range is likely an unrealistic goal. You can support her by listening to her voice and helping her sing in a healthy range and part.

- Post signs for gender-neutral bathrooms in rehearsal and concert spaces. Educate your chorus and audience regarding the protocol and importance of gender-neutral restroom space.

- Use gender-neutral language in rehearsal and ask that section leaders and singers also follow these guidelines.

- Update your guest artist and musician contracts to ask that guests use gender-neutral language when working with your chorus.

- Adopt a gender-neutral language statement for your organization.

- Invite all singers to audition for any solo that fits their vocal range.

- Include trans* and gender-nonconforming individuals, artists, speakers, composers and song writers as guest artists in your concerts.

- Examine requirements mandating gender-specific concert attire. Requiring singers to wear gender-specific clothing may be seen as a devaluing of identities and communicates indifference to the spectrum of gender identity and expression.

The physiology of trans* voices:

Singers who take testosterone as they transition from female to male (F2M) will experience a voice- range transition much like the one that occurs for boys during puberty. In puberty, the vocal folds lengthen and thicken, producing a lower voice. An F2M adult who takes testosterone experiences a thickening of the vocal folds, which lowers the pitch of the voice, but the vocal cords will not lengthen. As in puberty, it is helpful if F2M singers sing gently and consistently through the transition process. For singers transitioning from male to female (M2F), professionals disagree on whether taking estrogen can reverse the thickening of vocal folds, but the younger a singer is when she begins taking estrogen, the more likely that her range will move upward through a thinning of the vocal folds. Many M2F individuals are able to train their voice to speak at a higher pitch and some singers are able to train their voices to sing in falsetto, although this is more challenging and requires a skilled singer and voice teacher. Click here For more information about trans* voices on the GALA Choruses Resource Center.

- Not About Me - August 3, 2020

- Trans Opera - March 6, 2017

- Out of the Shadows - January 14, 2017